“Fix the Tired”: Cultural Politics and the Struggle for Shorter Hours

In the spring of 2012, McDonald’s began airing a series of commercials exhorting Americans not to “be a chicken” and to “take back your lunch!” The television spots feature a multicultural crew of cubicle slaves aghast at (but clearly a little seduced by) the audacity of the black woman inciting the mini-revolt and heading out to McDonald’s for a lunch break, telling the audience implicitly to join the woman, as an Asian male co-worker does, in striding out of the office and into the local Mickey D’s – here portrayed as an urban outdoor café.

The ads are part of the “It’s Your Lunch – Take It!” campaign, dominated on social media by red posters with messages like “A sesame seed of REVOLT has been planted,” “OVERTHROW the noon meeting,” and “Don’t Be a Chicken – Eat it!” And while much of the progressive blogosphere was horrified by the corporate appropriation of the revolutionary and disruptive discourse that’s newly in the air since the Occupy-dominated fall of 2011, the fact that one of the world’s most sophisticated market research and advertising design behemoths chose to sell burgers and chicken sandwiches by attempting to tap into Americans’ discontent with the contemporary crisis of overwork through which they have been suffering, speaks to something more than just McDonald’s craven pursuit of profit.

It is material evidence for a growing exhaustion on the part of the American working class, and, I’d like to propose, to the conditions for the possibility of its overcoming. The vast majority of workers in this country have seen their hours of work increase – about 180 additional hours per year in comparison to 1979 – and their average pay stagnate over the last thirty or forty years, and this trend has only been exacerbated as the Great Recession that began in 2008 effectively doubled the unemployment rate, so that those “lucky” enough to have a job have been, by all indications, working scared – which means longer, harder, and without much of a peep. In 2010, US worker productivity surged as a result of massive layoffs in the wake of the financial crisis (doubling from the 2009 rate, which was double that of 2008). This is not surprising – it’s a reiteration of a trend that’s been in evidence since the early 1970s, when the Keynesian wages-for-productivity deal between capital and labor was definitively called off. Now, with every crisis and subsequent “jobless recovery,” those fortunate enough to earn a paycheck in the aftermath tend to keep their heads down and accept doing the job of two or more people, “multitasking,” (which research shows is not actually possible), or, more and more, forgoing essentials of a decent life, of which lunch may be just a minor example.

This plague of overwork is taking a massive toll. Although pharmaceutical companies make a killing selling medication to ease the stress, the anxiety, the worry, the disconnection from friends, family, and community, and the general malaise that’s so prevalent today, it seems the pills are not quite doing the job as far as work is concerned. According to the American Psychological Association’s recent Stress in the Workplace study, thirty-six percent of workers experience work stress regularly and 49% attribute a significant part of this to low wages. But it’s not just the money – 43% of workers surveyed are unhappy due to heavy workload, 40% due to the unrealistic expectations of their employers, and 39% of workers report long hours as a major source of stress.

One-third of workers report having serious trouble balancing work and life – and like all surveys that measure unauthorized attitudes, this is most likely underestimated. Arlie Hochschild’s ethnographic work on families and children has for decades now made the case that overworked two-income families are dysfunctional from the perspective of happiness and of child development. In her recent work, “The Outsourced Self,” Hochschild discusses the penalties imposed on the personal sphere by “the unforgiving demands of the American workplace,” and finds that children – 70 percent of whom live in households in which all the adults work – are the most harshly punished of all. Hochschild quotes economist Sylvia Hewlett’s When the Bough Breaks: The Cost of Neglecting Our Children: “compared with the previous generation, young people today are more likely to underperform at school; commit suicide; need psychiatric help; suffer a severe eating disorder; bear a child out of wedlock; take drugs; be the victim of a violent crime.”

The increasing penetration of what Marcuse calls the “performance principle” – the imperative that every moment and every iota of the natural world be made to produce at optimum efficiency, an imperative that he sees, following Max Weber, as the defining feature of contemporary capitalism – deeper and deeper into the educational institutions means that kids suffer at school, too. Subject to an increasingly stressful regime of testing and homework that leaves many plagued by depression and anxiety, children and teens are increasingly likely to use performance-enhancing and mood-altering drugs in an attempt to keep up with it all. In fact, the newest drug abuse plague in middle-class high schools is the abuse of Adderall, an ADHD drug that helps the kids succeed. You know it’s a bad sign when teenagers aren’t even using drugs to get high, but just to focus and work harder. And the talk among the new billionaire educational “reformers” and the officials on board with their project is that what we need to do is eliminate summer vacation for kids! Children, it seems, are the canaries in our coal mine.

Speaking of a coal mine, stressed families and unhappy kids are only one of the deleterious effects of an overworked, stressed-out bunch of adults. The ecological costs of what economist Juliet Schor calls the “business-as-usual economy” are, it goes without saying at this point, severe. The environmental crisis that we face demands attention, presence, critical thinking – precisely the qualities that overwork and its concomitant stresses so severely impede. Our educational institutions are currently following in the disastrous footsteps of what Jock Young, following Marcuse, calls the “ethos of productivity” – the idea that anything worth doing can be quantitatively measured in terms of what it produces, rather than what it is in itself. This logic, when applied to the natural world, has ushered society into the era of chronic catastrophe. Planet earth has a brilliant ability to purify itself, innovate solutions, and heal from toxins when left, relatively speaking, alone. But the work ethic applies to everything – and no bit of mountaintop or shale rock or ocean is left just to be. From the perspective of capital, the natural world is a resource to be extracted productively or a dump for the effects of profit-making production. This productivist logic will, if not arrested, very seriously be the death of us all.

This ethic, having saturated elementary and secondary education with its relentless regime of testing, assessment, and endless work, now has higher education clearly in its sights, demanding an end to the “useless” thinking that characterizes a broad liberal arts education and an intensified articulation of the undergraduate degree to the requirements of corporations – the very corporations that make profit from the desperate overwork of their employees. Colleges and universities, at one time at least in part a space to develop thinking outside of the standard “good=profitable,” are being squeezed under a new regime disguised under the terms “accountability” and “outcomes assessment,” but which are really a strategy to bring one last somewhat intellectually unruly place under rational, and increasingly corporate, control. Public support for these policies is bought with the withdrawal of government funds from higher education, funding without which the expansion of higher ed from elites to a significant portion of Americans never existed, and probably can’t be viable. This is a central piece of the ruling class strategy of “starving the beast” – underfunding public services so that they don’t function properly, and then making a successful political case for their transformation and privatization, and it applies both to public colleges and universities and privates, which rely on public support to operate.

The plague of overwork and the culture that supports it has even more concrete consequences: people’s very physical safety is at risk. America fell in love with the heroic Sully Sullenberger after he successfully landed a jumbo jet on top of the Hudson River in 2009, but they didn’t listen hard enough when he testified before Congress soon afterward that if people want great, safe, experienced pilots like him to fly planes, they’ll have to join the pilots’ union in fighting for it, since the airlines themselves wage a relentless battle in every contract negotiation to allow planes to be flown by less-experienced pilots working 80-hour weeks for close to minimum wage. A few weeks after Sully’s “miracle on the Hudson,” a smaller, regional jet crashed in upstate New York, killing everyone on board and one person on the ground. It had been flown by two young, inexperienced pilots who were later found to have been suffering from fatigue. In another of many examples, New York City has just shut down a number of Chinatown-run bus companies for safety violations to which attention was brought by a horrific highway crash caused, it seems, by one of many exhausted and underpaid drivers. And “distracted driving” – otherwise known as the attempt to multitask behind the wheel – is now, with fatigue, the leading cause of auto accidents.

The explanation for all this is, in some ways, simple. Americans work 137 more hours per year than Japanese workers, 260 more hours than British workers, and 499 more hours per year than French workers. America is the only rich country without any mandated time off, and its workers continue to be the most productive on earth – working hard generally because they are working scared. Americans are working longer and harder than ever before, and than any other workers in highly developed nations. The reasons for this state of affairs are twofold: the decline of organized labor in the U.S. during the last quarter of the twentieth century, and the cultural ideology of the work ethic into which American workers, more than others around the world, are socialized.

The root of all this is a culture, first outlined by Max Weber in his well-worn but still fully relevant classic The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, of the work ethic, the idea that hard work in itself is a moral imperative and that laziness, in itself, is a sign of moral turpitude. America, more than any other nation, has been culturally shaped by the “spirit of capitalism” – the idea, as Weber says, “so familiar to us and yet really so little a matter of course,” that the combination of hard work and a compulsion to save and accumulate money characterizes the ethics of the morally upright man. What unites the two, hard work and penny-pinching, is an ascetic avoidance of any behavior that’s spontaneous or hedonistic. In this ethic, the good is identified with a detached, calculating attitude toward the moments of one’s life and our natural surroundings; the bad or unethical is identified with the “spontaneous enjoyment of life,” in whatever forms it takes. This ethic – the privileging of work, thrift, and calculating detachment over play, hedonism, and spontaneity was the characteristic feature of the Puritan culture that founded a significant portion of America (this largely accounts for the massive discrepancy between ours and the Europeans’ social wage and hours of work), and that is central to the operation of capitalism still.

For although our Protestant-based culture encourages us to equate being “productive” with being a moral, ethical person, the “work ethic” at this point is little more than a cultural strategy to dupe workers out of understanding the simple fact that what we’re seeing here is as old-fashioned as those McDonald’s ads are trying to look: the class struggle. In Weber’s analysis, capitalism, once it becomes dominant, no longer needs the ascetic culture that built the bourgeoisie. However, this Puritan class became so successful that their values, derived from Calvinism, are now a tenet of our culture. Americans are not working longer and harder for less because they necessarily believe it’s the right thing to do – but the cultural dominance of the work ethic demands at least lip service and punishes perceived resistance. And they are not working so hard because there’s not enough to provide for people outside of the regime of endless work, as the current scarcity-dominated corporate-funded media discourse would have us believe. Both in the long and the short term, it’s not real material scarcity but the unevenness of the struggle between capital and labor that accounts for where American (and increasingly, European) workers are today. Technologically-driven productivity gains make possible the ancient dream of human liberation from alienated labor. But it’s not automatic. Capital will just as easily take the gains in increased profits. How the fruits of productivity are socially allocated is itself the product of a struggle.

And by all indications, in the struggle between capital and labor, it seems that the bosses are winning the cultural as well as the material battle, in the US at least. However, the American work ethic is just never completely internalized by the working class, I would argue, because ultimately it’s an iteration of the logic of capital. Human beings do not live according to the same logic that corporations do. Simply put, there is an opposing logic at work within the capitalist system – what Stanley Aronowitz calls “the counterlogic of the working class.” If the logic of capital is the push for profit, and ever-greater profit through the exploitation of labor – more and more production for low and declining wages – the opposing working-class counterlogic becomes the locus of any real resistance to the crisis of overwork we’ve been outlining.

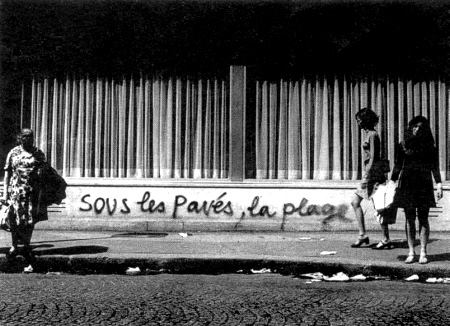

Antonio Negri calls this the “refusal of work” – the mass insubordination to capital’s demand that all moments of life and pieces of the natural world be alienated and made productive rather than enjoyed in themselves. For both Aronowitz and Negri, the essence of class struggle is everything that people do outside of and in opposition to the logic of capital. Harry Cleaver, in his introduction to Negri’s Marx Beyond Marx, puts it thus: “Capitalism is a social system with two subjectivities, in which one subject (capital) controls the other subject (working class) through the imposition of work and surplus work…therefore, the central struggle of the working class as an independent subject is to break capitalist control through the refusal of work…in the space gained…the revolutionary class builds its own independent projects – its own self-valorization.” This self-valorization consists of all the independent, self-directed activities that people engage in as a result of their own desires and aspirations and that are by definition antagonistic to capital’s push to increase profit quantitatively. Some is active and productive, some is passive and receptive, but it’s all a product of the individual constituting time on his or her own terms. It’s fundamentally different from the colonized time that constitutes life at work.

Even in times of an intensification of the austerity strategy of capital, keeping people working hard and working scared, the existence of this counterlogic remains easy to spot. The mobilization of it is another question, to be discussed below. But there are certainly plenty of contemporary signs pointing to a subterranean resistance to the demand that all life be subordinated to paid labor.

In fact, a discourse around shortening the hours of labor is emerging to make sense of both the double crisis of overwork and unemployment, and of the subterranean resistance to this state of affairs. The largely unthreatening TEDtalks have even gotten in on the action – with one popular recent talk extolling the importance of work-life balance and even of leisure, but minus any discussion of the history of the capital/labor struggle over work time the outcome of which actually determines how long and how hard people are working. Similarly, in early 2012, The New Economics Foundation, a British think tank, came out for a twenty-hour workweek as the solution to the technological displacement of jobs, the stress on workers, families, and communities, and the ecological costs of rampant growth fueled by incessant work. One of the authors of the report asserted that “there is a great disequilibrium between those who have got too much paid work, and those who have got too little or none.” The report got a great deal of play as an innovative idea that made sense. But there was very little discussion of how a twenty-hour week might be accomplished aside from the usual milquetoast “government should mandate it.” That exhortation might be a nice way to end a paper, but it’s no strategy for social transformation.

In June 2012, the front page of the New York Times Sunday Review section featured an article titled “The Busy Trap,” which pillories the culture of equating being “crazy busy” with having a life that matters; the author finishes his ode to idleness and pleasure as the essence of a truly human life with the assertion that “life is too short to be busy.” That same month, highly influential left-wing talk show host Bill Maher ended his show with a lamentation that America is “the only country where no one really gets the day off.” Pointing to the six-week paid vacations and mid-day siesta breaks among Europeans, he answers his own question – why the difference? – by asserting rightly that Americans are working scared, terrified to lose their jobs because we’re the only “big-boy” country in which unemployment means total destitution. And unlike many of those who criticize overwork, he acknowledges that it’s the decline of the union movement that accounts for this pitiable state of affairs.

The problem is that the organized labor movement has been in massive decline for decades, under relentless attack by the union-busting and outsourcing that have characterized capital’s post-1973 neoliberal agenda.

The bumper-sticker version of this insight puts it simply: “The Labor Movement: the folks who brought you the weekend.” It’s important to remember that the labor movement and the question of hours are linked not only in terms of the problem of overwork but also of its solution. According to David Roediger and Philip Foner’s “Our Own Time,” a seminal study of the movement for shorter hours within American labor, “the length of the workdays has historically been the central issue raised by the American labor movement during its most dynamic periods of organization.” The authors go on to demonstrate the way in which the demand for shorter hours of labor, both as a means to share the work during times of high unemployment and as a means to the enjoyable life that capitalist “progress” can technically make possible with a minimum of toil, has been the most inspirational demand that the movement has ever put forth.

And according to Jonathan Cutler, author of Labor’s Time, a study of the shorter hours movement within the 1950s United Auto Workers, when after much internal struggle the union effectively abandoned the syndicalism of the hours demand for Walter Reuther’s corporatist strategy to make labor a partner in managing production (and society), it lost its ability to inspire and thus to mobilize workers in the face of increasing employer aggressiveness. According to Cutler’s analysis, the demand for a thirty-hour workweek at forty hours’ pay was consistently the most popular issue among the union’s rank and file. He argues that the demand, in addition to potentially ameliorating the desperation accompanying unemployment, is inherently solidaristic across lines of race, ethnicity, and gender – lines that capital has always used to divide and conquer the working class. Roediger and Foner again:

“Reduction of hours became an explosive demand partly because of its unique capacity to unify workers across the lines of craft, race, sex, skill, age, and ethnicity. Attempts by the employing classes to divide labor could be implemented with relative ease where wage rates were concerned…With regard to hours, the situation was different…thus the shorter working day was an issue that could mitigate, though not completely overcome, the deep racial and ethnic divisions that complicated class organization in the United States.” (viii)

McDonald’s implicitly argues this with the fascinating racial politics of its “take back lunch” campaign – gender and racial-ethnic difference is elided in the appeal to a seemingly universal desire for leisure.

Fundamentally, the question of hours is a question of labor supply, and a shorter hours strategy is a push to restrict the supply of labor provided to capital while avoiding the unsustainable exclusions of the old AFL craft union version of such a strategy. In order for a push for a shorter work day or week to be successful, everyone has to be in. Everyone has to contribute to the withdrawal of labor supply, which is both a means to the leverage provided by an undersupply of labor relative to demand, and, crucially here, something valuable in itself. And the inherent solidarity of the strategy extends to the unemployed as well: as AFL President Samuel Gompers said in 1887, “so long as there is one who seeks employment and cannot find it, the hours of labor are too long.”

The globalization of capitalism makes this solidaristic labor supply strategy even more crucial, as the fortunes of one nation’s workers are increasingly, and more and more visibly, tied to those of all other nations. Any “us” and “them” strategy pits workers against workers in an ugly race to the bottom – we have to work harder to compete with the (fill in the blank) workers who work more for less! This is precisely the reason that if the organized union movement wants to successfully mobilize the resources it still commands – 16 million members and over ten billion dollars in dues revenue, still not quite something to sneeze at – it must rethink many things, from its codependent relationship with the Democratic party specifically and fetishizing of electoral politics more generally, to its focus on defending the benefits of its own members rather than on a broader working-class strategy, to, most important, what Aronowitz has criticized as its focus on “jobs, jobs, jobs.” The latter is just not what moves people. Movements need many things, but an inspirational discourse is central to success. Defending and demanding more jobs has just not really cut it. The history of the labor movement, as I see it, shows that a push for freedom does.

There is plenty of evidence that the popularity of the shorter hours demand would be even more powerful today than it ever has been. For one thing, the fact that productivity growth declined by .9% in the first quarter of 2012 even though the high unemployment rate barely budged, seems to be a sign that the strategy of working folks to death may just be hitting a wall. The market research firms that drive big advertising certainly seem to think so. An ad for Carnival cruise lines features a middle-aged dad letting loose on the dance floor to the tune of “I Don’t Want to Work,” as his son’s voiceover reflects on how “different” dad seems on vacation. “What’s going on with dad?” the boy intones over images of the father laughing and goofing off with his kids and romancing his wife. “He seems different. He’s not tucking in his shirt. He’s not talking about work. He’s not checking messages every nine seconds…and now this?” over images of the father letting loose on the dance floor.

This is one of many leisure industry ads that focus especially on the personal joy and family connections that leisure promotes and overwork warps. Corona beer commercials for years now have used the popular metaphor of the beach for leisure and relaxation and counterposed this image with those of the workaday world, from which it is assumed that viewers want a respite (and can supposedly get it by drinking a Corona – which is a start.). Dorito’s is currently selling tortilla chips with a spot in which the cheetah mascot joins two construction workers in disco dancing around a construction site and joyfully ignoring the impotent boss’s exhortations to get back to work. And a new “Take Back Your Summer” ad campaign for Las Vegas dramatizes a grim-looking workplace ceremony in which a silver-haired boss awards a middle-aged man with a certificate honoring his not having taken a vacation day since 1997. The worker responds by screaming “Certificate? Certificate?” and running around the room, ripping up said certificate and the sad-looking “celebrate” sign hung comically in the corner. The ad ends with an image: “Vegas. TAKE your vacation!”

Other ads in the campaign highlight workers “making their escape” from their dehumanizing offices, breaking out of the workplace paramilitary-style as though it’s a prisoner-of-war camp. A few spots, significantly, are more explicitly political: a worker stands on her desk, Norma Rae-style, holding up a “Vacation Now” sign and saying “I have 47 vacation days! That is insane! They’re our days! Let’s take back our summer!” Another depicts a well-attended rally about which one participant explains, “we’re rallying everyone to use their vacation days this summer…how many do you have?” Assorted workers – white collar, construction, and service – tell how much vacation time they’ve accumulated but never used, because, as one of the workers says in another spot, “nobody takes their vacation days.”

Significantly for the way this politics plays in terms of the Social Security/retirement age debate (one of the most important contemporary questions of labor supply and work vs. leisure), an older fellow bikes up to the rally and asks, “I’m retired. Can I take a vacation?” One can practically hear the shrill conservative response in the awkward pin-drop silence that follows the question. When a rally leader cries, “sure. You’ve earned it!” and the rally explodes in celebration, the commercial implicitly demonstrates the political reality that to the extent that the retired and the working refuse being pitted against one another, everybody can enjoy the leisure that they’ve “earned.” The existence of all these cultural representations of the counterlogic are significant, not just as indicators of the continued subterranean refusal of work that Negri says defines the working class, but also in terms of the kind of real movement activity that images of this refusal can, potentially at least, inspire.

First, all these commercials provide more evidence to refute the idea, widely accepted in left circles, that advertising in particular and commercially-produced culture more generally, has no subversive political content. I’ve argued elsewhere (cite) that it’s high time for progressives to abandon the idea that consumer culture functions only to prop up the current, exploitative capitalist order, the very one that keeps the masses chained to their cubicles (or wherever they work), whether in its Birmingham incarnation – which posits that cultural opposition, like the punk rockers that the BCCCS famously studied, to capital is “real” but inevitably gets swallowed up by the system and packaged for sale, stripped of any but surface, meaningless opposition – or in its more recent, Thomas Frank-generated version, outlined in his 1997 The Conquest of Cool, that posits that oppositional culture is actually a product of the hucksters on Madison Avenue, because if a person wants to be “cool” and distinguish him or herself from the masses, that person must continually buy something new in order to maintain this distinction. Either way, rebellion is just another mode of incorporation into the system.

However, the truth is that the significance of commercial culture transcends that function. As Ellen Willis said of the sixties counterculture, arguing against “standard leftist notions about advanced capitalism – that the consumer economy makes us slaves to commodities, that the function of the mass media is to manipulate our fantasies so we will equate fulfillment with buying the system’s products,” she asserts that “these ideas are at most half true. Mass consumption, advertising, and mass art are a corporate Frankenstein; while they reinforce the system, they also undermine it…the mass media helped to spread rebellion, and the system obligingly marketed products that encouraged it, for the simple reason that there was money to be made from the rebels who were also consumers. On one level the sixties revolt was an impressive illustration of Lenin’s remark that the capitalist will sell you the rope to hang him with.” (emphasis mine)

As much fun as it is to trace the way that advertisers tap into the subversive tendencies afoot in American culture, though, having these tendencies broadcast widely by hucksters is simply not enough. For one thing, the capitalist will as just as easily sell you the rope to hang yourself with. For the Vegas commercials and their ilk may be getting more prominent, but they are by no means the only ones on television. Campbell’s soup advertises a liquid food that you can drink at your desk or wherever it is you are hurrying off to. There is even a toy foot spa for little girls, called Orbeez, the ads for which portray pre-teen girls stressed after a hard day, trying to relax by bathing their feet. Assorted television, radio, and print spots support the still-dominant discourse that there is an individual solution to the structural problem of what might be called the “energy crisis” of the overworked American employee. In this case, the advertisers are tapping into not subversive desire but the exhaustion and desperation felt by time-poor workers of all stripes.

One of the most ubiquitous aims to sell “Five Hour Energy,” a liquid stimulant that comes in single-serving plastic bottles meant to be ingested in one quick quaff. The advertisements have many iterations, but generally hew to the same theme. A typical one opens with a classic blues soundtrack, wailing, “I’m so tired…” behind images of workers of all collars wilting from exhaustion at their desks and on construction sites. The gravelly-voiced, oh-so-sympathetic narrator gives voice to what we all know: “Tired sucks. Not end-of-the-long-day tired, but middle-of-the-day, places-to-go, things-to-do, deadlines-to-meet, but all-I-want-to-do-is-close-my-eyes tired. Five hour energy fixes tired fast. One shot. Back to work. Problem solved. Five hour energy. Fix the tired.”

Probably the most discouraging ads, from the perspective outlined here, are the spots that highlight workers who simply don’t have the time to brew even the morning cup of coffee with which sleep-deprived workers fuel their workday, and used to at least feel they had the time to enjoy. In another spot, a bed-headed young woman is trying to find the energy to work out on her home exercise equipment – an activity broadly encouraged these days as one of the things that can make people happier and more productive under the stressful circumstances. Five-hour energy makes it possible for her. It seems only a matter of time before the little stimulant is portrayed as the way people can find the energy to do yoga, or meditate, or any of the other new-agey ways that will purportedly make its practitioners more “sane” and “relaxed.” Can the 5-hour energy solution for finding the energy to pick up the Prozac bottle to make tolerable the misery of overwork be far behind?

Sadly, the five-hour energy “solution” is emblematic of much of what is discursively held out to workers as the way to navigate this disastrous state of affairs. Along with ingesting the little drink (and then throwing away the hard plastic bottle), we are exhorted to get yet another debt-funded degree, to work harder, to stay at work longer, to multitask better, and to forget everything else that makes life worth living and spend all of our time working to afford student debt, food, gas, and health care.

A Hormel ad campaign celebrates this explicitly: one of its “Hardest-Working Women” ads begins by panning over a cubicle decorated with family photos and drawings by children. The woman at the desk looks a little tired but determined; the narrator intones: “Your desk. It’s where you spend a lifetime. So your kids can go to college. So you can actually visit that beach displayed proudly on your monitor. For that, you work through lunch. Or, as we like to say, lunch through work.” The microwave meal is touted as “desk drawer to hot and ready within 90 seconds.” And the campaign includes a “hardest-working woman” contest, in which family and friends are invited to nominate hard-working women to win a 3-day trip to NYC (flying coach) worth approximately $4,900. The winner receives a makeover and a spot on Oprah’s new show, and a certificate that reads: “Today we celebrate Crystal…Crystal puts in long hours at the medical clinic that she runs, is an active mom to three young children, serves as her daughter’s Girl Scout troop leader, donates to charities and is a serious couponer. According to her husband, she puts all of these responsibilities before herself time and again.”

Clearly, advertisers know that there are two tendencies out there: docility born of desperation (especially among women, still largely responsible for the second shift at home), and resistance born of the far more utopian desire for freedom. They are agnostic with respect to which tendency is preferable – in this, the commercial side of capital is a highly unreliable ally of their class brethren, the bosses. However, the workers to whom they ply their messages are not agnostic on this issue. Appeals to both tendencies abound within commercial culture: both desire and fear drive working-class strategies in the contemporary absence of a vibrant labor movement. As American Studies scholar Michael Denning puts it, “subaltern experience does not necessarily generate social criticism and cultural resistance; the possibility of popular political readings of cultural commodities depends on the cultivation, organization, and mobilization of audiences by oppositional subcultures and social movements.” (p 64 CF)

Denning’s work on the cultural politics of the CIO period’s Popular Front are instructive for those who are interested in mobilizing the resistance that’s potentially always afoot. What he calls the “Cultural Front,” the organization of artistic and intellectual spaces and activities in support of the labor movement and the revolutionary politics of the Communist Party, points to the crucial role that cultural politics has always played in successful working-class resistance to capital’s logic of seeing every iota of the lifeworld as a means to the end of making profit.

Advertisers understand something quite profound about generating collective action: when you appeal successfully to a deeply-held desire, you have the ability to move masses of people to do the same thing, all at once, and without an endless meeting, no less. For the advertisers and the corporations they serve, the collective action involves masses of people buying the same thing all at once. But this is certainly not the only kind of collective action that people can be inspired to engage in, and in the most vibrant moments of working-class resistance, organizers have understood this principle. The politics of a culture of freedom from work, of values that are incommensurable with a logic of profit-making, are key to any successful mobilization.

And this is true not only of what’s called the Old Left, but of the (now-old) New Left as well. In fact, as twentieth century history, I think, clearly demonstrates, the key moments of working-class uprising in the US have been combinations of labor organizing and the cultivation of a culture in which values – like art, freedom, pleasure, connection – that can’t be quantified in a profit-loss balance sheet are dominant. Union struggles, from the uprising of 20,000 in 1909 and the Paterson strike of 1913 to the CIO battles of the thirties and forties, to the shorter hours struggles of what Aronowitz has called “The Unsilent Fifties,” to the hippie resisters of alienated work that engaged in the famous wildcat strikes at the Lordstown, Ohio General Motors plant in 1972, to the more recent conjoining of the radical cultural space that was the Occupy encampments with the union leaders and members who saw these extremely bohemian and radical spaces as their best hope – are most powerfully supported by the cultivation of what might be called the cultural politics of the class struggle. In those periods as in the current one, successful working-class resistance to the austerity of decreasing amounts of free time as well as of work’s material rewards depends, I am arguing, on the active organizing of a cultural resistance to the domination of human energy by work, by its being put to use for the purpose of profit.

For those who would oppose the quotidian, life-wasting horrors of overwork and austerity and the cultural ideology of work that curbs the opposition to these things, the Occupy uprising of fall 2011 was an auspicious sign of things to come. In the Occupy spaces (the frequently quite brutal global shutdown of which speaks, it seems clear, to their subversive power), old-fashioned labor movement discourse like “general strike” and “port shutdown” came together with a drum-circle utopianism that said things like “the beginning is near” and “music, not austerity.” And although Occupy was a flowering of the most recent incarnation of the anarchist tradition in radical politics – the not quite aptly-named “anti-globalization” movement – and internal debates on the left see anarchism and a more traditional radicalism as somewhat opposed, Occupy Wall Street was in many ways a space organized in the best, transcendent tradition of the American left. Within the Occupy spaces, first of all, everything was shared. And most important, between the cultural politics of opposition to capital by the “99%” – free association, eating together, conversations with strangers and music and free books and creativity and good times – and the union movement itself, for a time, there was little daylight.

Occupy, despite the stated desire of many of its key activists to eschew the “old” left, is in many ways a reiteration of the best of the left tradition in the US. It is a powerful cultural movement which has definitely changed the way class and power are discursively framed, and in a moment in which corporate profits have never been higher and wages as a percent of the economy are at an all-time low, it is key that people are clear on what Negri calls the “logic of separation” that constitutes capitalism – the essentially antagonistic interests of labor and capital. Its practitioners definitely get the terms right – calling for a “general strike,” for folks to “occupy everywhere,” and inspiring a level of militant activism not seen in the US for some time (its global connections and deployment of new social media are totally new – and could just portend the fulfillment of the radical dream of Rosa Luxemburg and the IWW for a truly global working-class movement). Summer 2012 will see the “Occupy Guitarmy” stage a “99-mile march” from a National Gathering at Independence Hall in Philadelphia to New York City in honor of the one-hundredth birthday of Woody Guthrie, America’s emblem of the power of cultural opposition to fuel on-the-ground labor agitation, and vice-versa.

Today’s nascent coming together of cultural and labor radicalism points the astute observer back into the most successful moments of the US union movement – the struggle for freedom in time and the material abundance that capital makes technologically possible even as it disavows this potential in favor of the discourse of artificially perpetuated scarcity in order to maintain control over an always potentially restive working class. To the extent that those interested in arresting the trend toward overwork and desperation among the American, and global, working class, can see that the most progressive moments for American labor have been the ones in which labor and its representatives embraced the counterlogic that opposes capital’s relentless instrumentalization of human life and nature, and the countercultural organizing that mirrors this, the new movement will have some very useful history to peruse, despite the desire of many Occupy activists to ditch what they see as a creaky, cranky old left. Something crucial unites the bohemian modernism of John Reed and Emma Goldman’s early twentieth-century Greenwich Village, the proletarian avant-garde of the popular front, the shorter hours enthusiasm of the auto workers in the fifties, the hippie work resisters of the 70s, the rock and roll “slackers” of the nineties, and the free-living Occupy anarchists of today: it’s a subterranean, utopian refusal that’s always available for successful mobilization that radicals should by no means leave to McDonald’s and Dorito’s to profit from. Advertisers are hedging their bets on which is the more powerful popular mover – desperation or desire. Right now, they’re playing both sides. If the American union movement embraced its own most powerful traditions – radical cultural organizing and the push for shorter hours – I’d say the smart money would bet on freedom.